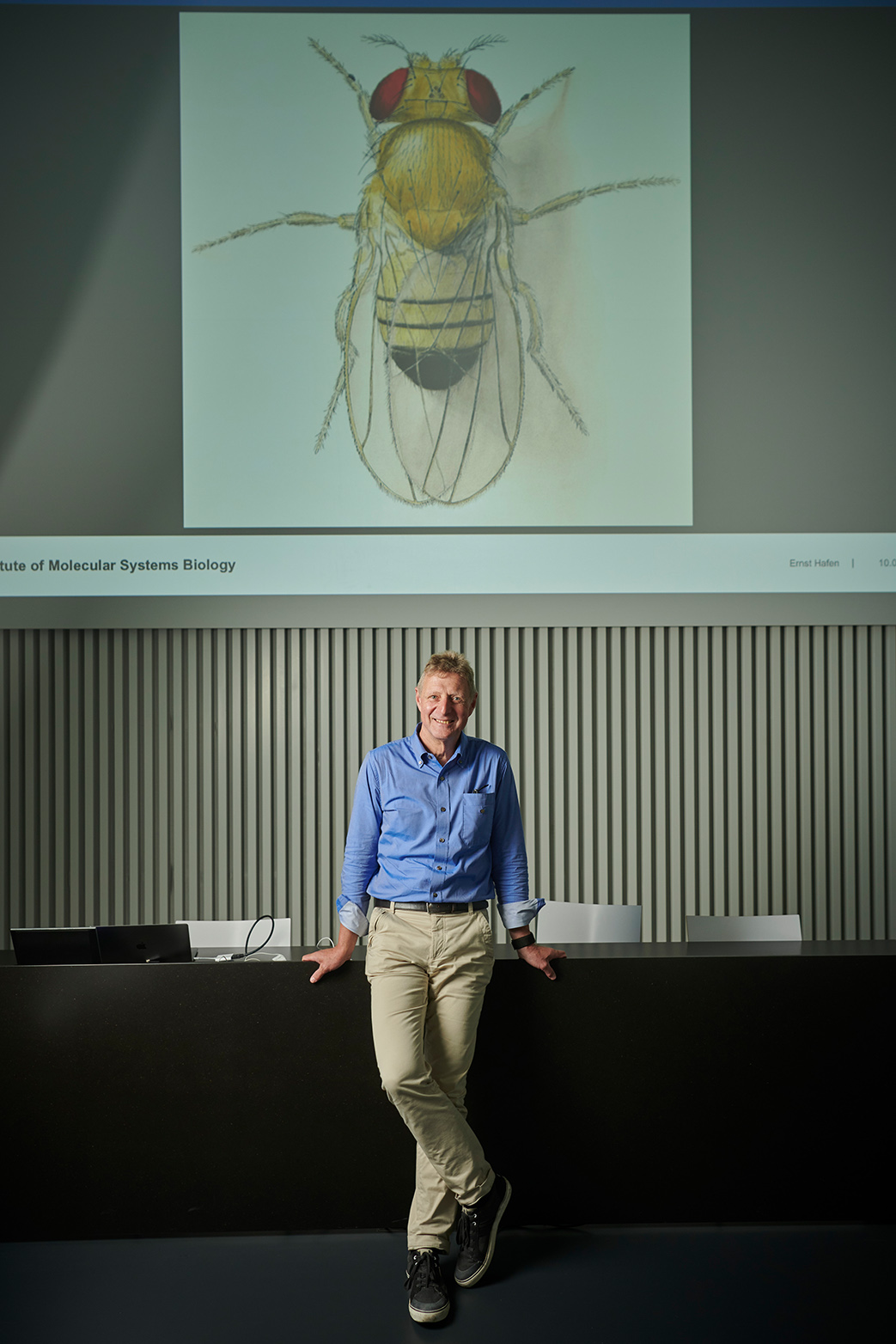

Ernst Hafen made his scientific breakthrough with the fruit fly Drosophila.

This discovery also gave his doctoral studies a new direction: genetics as a method for understanding developmental biology. “I was fortunate to work with two American postdocs, Mike Levine and Bill McGinnis.” This was a formative period for Hafen: he immersed himself in the lifestyle and ethos of Levine and McGinnis. “Those two showed me a whole new world. They had a different work culture. Life in the laboratory was more exciting than life at home. Sometimes we sat in the lab at three in the morning, smoking and drinking beer together.” After finishing his dissertation, Hafen moved to America to take up a postdoc position in Berkeley in 1984. It was during this period that he discovered a gene in flies that was known to be a cancer gene in humans.

After three years in the US, Hafen and his wife, along with their first two sons, returned to Switzerland, where their third son was born. He had applied for the post of assistant professor at the University of Zurich Institute of Zoology. Following his initial appointment in 1987, he was made full professor in 1997.

One year as ETH President

But Ernst Hafen was not just the “fly doctor”, as his son Timothy once called him when asked by his teacher about his father’s profession. “I always had a lot of different interests, including university politics,” he remarks. When ETH Zurich was looking for someone to succeed Olaf Kübler, due to step down as ETH President at the end of 2004, Hafen’s application was successful. He took up office on 1 January 2005, at the same time giving up his job as professor at the University of Zurich.

The ETH Board asked Hafen to reform the university along the lines of the Anglo-Saxon model. However, this ambitious reform project met with stiff opposition from the ETH professorship especially, and eventually came to nothing. This prompted Hafen to step down prematurely after just one year in office.

Back to studying flies

He stayed at ETH and was appointed professor at the Institute of Molecular Systems Biology, headed by Ruedi Aebersold, his friend and colleague since student times at the Biocenter in Basel. Their paths had separated while they were still studying: Aebersold started working with proteins, and Hafen with genes. However, Hafen was instrumental in persuading the pioneer of proteomics to return to Switzerland in 2004 and then take charge of the newly founded Institute of Molecular Systems Biology in 2005.

His appointment also benefited Hafen, by helping him find his way back to fly research. Hafen initiated “WingX”, a subproject of “SystemsX.ch”, the Swiss systems biology initiative launched by Aebersold. Its goal was to discover how an entire genome interacts in order to determine the size of the fly wing in a natural population of Drosophila. “With this project, we were able for the first time to study not only the effect of individual genes, but the interaction of the entire genome, all gene transcripts and the proteins based on them,” Hafen recalls. This had never been possible in such detail before. “It was only possible because I worked at the institute and was able to collaborate with Ruedi Aebersold. It was an excellent arrangement for basic research into flies.”

Data – a new hobby horse

After stepping down as ETH President, Hafen focused increasingly on questions and problems that had nothing to do with his research on flies: the treatment of personal (health) data.

More and more data about genomes, health and disease are now emerging not only from research and healthcare, but also from private individuals – the advent of smartphones and smartwatches continuously measuring body functions and movement. ”Each of us has the right and opportunity to collate far more personal health data than Google would ever be able to and make it available to our doctor or for research,” Hafen stresses.

He has noticed, however, that people leave the gathering together of their personal data to the tech giants, and he is campaigning against this: